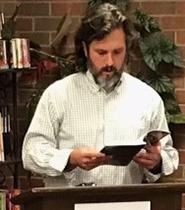

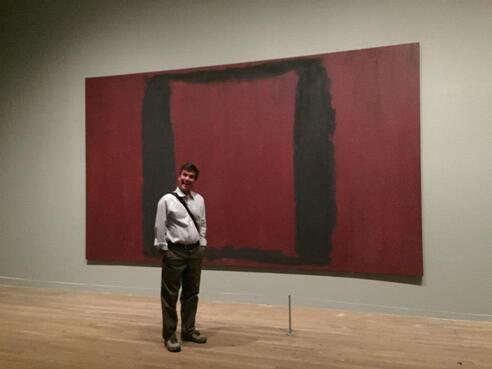

Jonathan Minton is a slender man. He looks much younger than his fifty years – not quite so young that he could be mistaken for one of his undergraduate poetry students at Glenville State College, but he could probably frequent the same bars people their age do and not look too out of place. His dark hair falls around his shoulders, lines of gray streaking through like lightning bolts. The classroom is clinical feeling in design with lighting and walls that would look at home in a hospital room. There is a whiteboard at the front of the classroom, but it goes unused, as does the projector, and there are no decorations to indicate that any one person might call this place home. The only sources of life in the room are the teacher, the students sitting in a circle. He has an easy way of speaking with students, not getting rattled if they don’t have answers or are mistaken. Answers delight him, and he is likely more forgiving than he should be when the mouths of students fail to produce correct responses or responses at all. He bends where others might break. Here at Glenville State, a small liberal arts university tucked into a West Virginia mountain town so tiny it boasts a singular stoplight, Dr. Jon Minton is a staple of the English department: department chair, running the college’s literary magazine, The Trillium, and the Honors Program. He previously sponsored the student club The English Revolutionary Society. Sometimes there are those in positions of leadership who seem to have been born to do it, whose imposing figures or family connections or tireless personalities push through into the future, demanding they be an important part of it. Jon Minton is not one of these people. Instead, as is often the case, he was the one willing to do the work, and so the work fell to him. You can see this in the way he wears the weight of responsibility – not quite comfortably, but perhaps more admirably because of the discomfort it requires. Dr. Nancy Zane is a woman who is stern and fiery in turns but always brilliant. She met Minton when he was hired nearly two decades ago to work as an associate professor at GSU, and they would work together until her retirement in 2016. “Professionally, he was all one could hope for,” she gushes. “Witty, bright, creative, publishing, conferencing – and why?” Because, she emphasizes, he wanted to do the things, not get whatever accolades or recognition or advancement they might earn him. There is a twinkle in Jon Minton’s eye. Despite his years on Earth and the tremendous strength it takes to remain gentle in a world that rewards brutality from its men, he has yet to lose his childish sense of wonder. “He is someone you always want to protect,” Zane confides, “even though he is perfectly capable and able to take care of himself.” This desire is echoed in others who know him, and it may be that the sense of wonder he maintains has been lost to so many of them that to see him walking around with it exposed to the elements triggers a desire to protect it, that the spark might never burn out; it makes you want to shield it from them, like hands against sunlight blinding your eyes or a sturdy wall against the raging wind. Despite that desire, Zane commends Minton for his distinct brand of tenacity. Minton is “brave enough to show his gentle soul to the outside world,” she continues. “I admire that kind of courage.”  Minton was born in the seventies in the foothills of Appalachia in Wilkesboro, North Carolina, best known for the music festival MerleFest. It was a quintessential late 70s and 80s middle-class upbringing, the imagery of a nerdy childhood something out of Stranger Things. He spent his time absorbing the works of Tolkien and comic books, playing Dungeons and Dragons, and marveling at the new Star Wars franchise. You can imagine his slight child-form there in the movie theater, quiet among crowds, mouth agape, delighting in the fantastic vision realized before him, allowing his mind to explore places previously unimagined, possibilities uncontained. As an adult, he would grow up to love films, but not only the good ones that have high ratings on RottenTomatoes and the even better ones that can be found in the cozy basement of the local indie theater. He’d come to delight in the worst that film can offer, movies so bad they feel good, or at least scratch some horrible itch, and he’d use his love of classic horror to create a series of poems that would celebrate that love, those fears. The forthcoming book of poetry will be called Famous Monsters, and it will explore 1980s slasher films and how they relate to literary history, social dynamics, and myth. Friday the 13th is broken into a series of poems; “the first gods were made out of fear,” one tells us, and we believe it, knowing something deep within understands the truth of this better than we, miles and years outside the cave, ever could. Poetry came to Minton in adolescence when he read Robert Frost’s “Bereft,” a brief but haunting piece that ends with the sobering lines, “Something sinister in the tone Told me my secret must be known: Word I was in the house alone Somehow must have gotten abroad, Word I was in my life alone, Word I had no one left but God.” It is perhaps when we are teenagers that we feel most exposed to loneliness, and so it is not surprising that these lines might have plucked at something inside of Minton, struck him as something worth holding on to. “There was a mysteriousness and an honesty in its approach to grief that fascinated me,” he tells me of how those lines hit him all those decades ago. “It still does.” Still, he wouldn’t take poetry seriously until years later when he took his first creative writing course as an undergrad at North Carolina State. Under the tutelage of the poet Gerald Barrax, Minton realized that his feelings and ideas would be at home only in the words of the poetry he could produce. “I had to focus there,” he says, referring to the pages where he’d write his own poems, “and push the syllables around to find their music or meaning or whatever alchemy I could muster.” Music, too, would be a big influence on both his person and his poetry. In his youth, he would fall in love with the punk scene, becoming a lifelong devotee to the likes of The Velvet Underground and Nico and The Ramones. “I can remember listening to PJ Harvey’s “Driving” in college and then attempting to use her syntax to create a similar sense of urgency in the poem I was working on. I’m not as deliberate in that way these days,” he adds, “but when I’m not writing, I stay in a poetic frame of mind by listening to music. You can’t listen to Nick Cave or Patti Smith for very long without finding something to write about.” I put on “O Children,” let Nick Cave’s gravel and The Bad Seeds’ symphony wash over me, and I believe him. When Minton speaks of learning his craft, he credits the brilliance of his teachers. The rest of the above “You Told Me What Was Essential” is both a love letter to and a celebration of their direction and how it forged a way forward for him into the world of words. “My first teacher, Gerald Barrax, told me to carve a poem from something true, then carry it, deliberately, as across a bog, as if someone’s life depended on it. Robert Creeley advised tactics over strategy, a fox in pursuit or in chase, not a commander drilling his soldiers, as if it were enough to think about where you are pointing, without ever stepping to it, or beyond what is torn, to find another ground. Charles Tomlinson said the world is wavering, there, as if someone had pulled a bow string, and you could feel the tempered wood trembling with it, a sequence of occurrences, always to be believed, but never possessed.” This love has been passed on to the students he has helped develop into writers and teachers and other professionals, and many of them who have graduated and moved on have nonetheless maintained a friendship with him, citing his kindness and compassion and sense of humor that’s “a little on the darker side.” Years after they’ve exited his classroom, his former students have reached out to him for everything from letters of recommendations to support while going through some of life’s most serious transitions. One boasted of having a key to Minton’s house, noting that Minton, a vegetarian, has eclectic taste, though his refrigerator is often bare. It is maybe this disinterest in food that has kept his figure so boyish, even as the grey weaves its way into his hair and sometimes beard. Another student credited him with saving his life, Minton’s kindness a bridge the student could tread on over a river of despair. It is not only former professors who have influenced Minton, though. Among Minton’s influences are Yeats, who made him want to be a poet, “and still does,” and two more recent poets: Charles Tomlinson and Cole Swensen. Intelligence and generosity are key to Tomlinson, Minton says. “He’s always in the margins of what I’m writing.” Of contemporary poet Swensen, Minton offers nothing but praise, saying, “Whenever I read her latest book, I feel as if it’s the very thing that I’m trying to do, only several steps ahead of me. Her work has always been a kind of true north for me.” He recommends picking up her book Such Rich Hour, and reading it all at once, turning the book into a single poem you can dissolve yourself into. I ask him if he has a favorite among his many poems, and he says his favorite is whatever one he’s working on. “I tend to get blinded by it.” He does, however, have one poem that he credits for changing his trajectory as a poet and opening up possibilities for him: “Landscape: On Charles Tomlinson,” a response to the work of the poet he so admired that plays with shape and form to create something meticulously crafted and includes a nod to bird skulls, the bird being a motif that will feature later on in his book of poems, Technical Notes on Bird Government. Of that collection, author James Capozzi says, “Testing the language of myth, the naturalist, and the historian, Technical Notes for Bird Government taps into a vast, skeletal architecture underpinning the hugeness of the world, and its wounded places where we vanish.”  Minton has lived many places in and explored much more of the hugeness of the world. The wounded places we might vanish into, that fearful loneliness Frost opined on, maybe aren’t all that’s left for Minton, though. When I ask about family, he lists his partner, Sabine, their assorted pets, and a large extended family with more cousins than he can name. When I ask where he feels most at home, he has several answers: Weston, WV, the small town he resides in; North Carolina, where he grew up; northern France where his partner hails from. They travel together when they can, he and Sabine, to China or France or wherever else might beckon to the pair. “I can't imagine writing without it being informed by travel,” he says, reflecting on the spaces he has existed in. “For me, there is no poetry without a sense of place. I can remember moving to Montana and feeling very inspired and challenged by those massive mountains, those mountains that seemed impossible.” He knew they would change the way that he wrote, and they did, their stunning combination of sharpness and steadfastness helping shape him into something quietly remarkable. When he isn’t traveling or running the English department or watching terrible movies or writing experimental poetry, he is editor of the literary journal Word For/Word, which he credits for changing his writing in ways that are immeasurable. Established in 2002, the journal has been a constant for Minton for nearly two decades. “I can’t imagine being a writer without it. In periods of writerly 'drought' in which I wasn’t writing much, it kept my mind focused on poetry in ways that probably wouldn’t have happened for me by just reading. And getting to work closely with so many utterly brilliant poems and writers and artists has been a gift. It’s become an essential, inseparable part of my writing.” What beauty have we, the reader, gained from those hours spent toiling shaping the lines of others only to be paid to us in poems? What can we take from the treasures laid softly into our hands, sacrifices to our altar of judgment? Whatever might be in our grasp as we diverge from the path we walk on the page with Minton, we must believe that it is more than our hands would’ve held otherwise. We have seen a gentle spirit face the darkest specters, loneliness and invisibility and responsibility unsought, and come out on the other side with his light still intact, a brilliance in the eye and a smile at the corners of the mouth. “Dear reader, we were lonely, and became characters in the dark, like flowers crawling up a wall. We’re more than our sentence. We’re more than this mouthful of air. If you’re telling me there are rivers moving between us, I will believe you. We fill the gaps with what we think should happen.” - Jonathan Minton, from LETTERS

5 Comments

4/16/2022 06:41:20 pm

Wow! I had not heard of Jonathan Minton but your piece is so well-written and interesting It’s made me want to find out more! Thank you!

Reply

7/12/2022 02:41:48 am

PhenQ diet pills for weight loss @ http://www.guideonproduct.com/phenq-review.html

Reply

7/12/2022 02:43:09 am

https://public.bookmax.net/users/lucysup/bookmarks

Reply

7/12/2022 02:48:49 am

Natural weight loss product https://bookmark4you.online/profile/submitted/shivaguideon

Reply

7/12/2022 02:49:28 am

Garcinia Cambogia Ultra Slim@ http://www.guideonproduct.com/garcinia-cambogia-ultra-slim-review.html

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Where I put pen to page, so to speak.ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed